The pipe organ has always been considered an instrument relegated to the Catholic Churches for the Catholic Churches, in reality, the dignity and history of this instrument are much deeper and more interesting.

Its importance in the literary, archaeological and figurative fields shows an instrument with precise political and diplomatic features, such that it is a sound image of the imperial power of Ancient Rome.

The History of the Pipe Organ in Music is intertwined, often, with other topics and areas, also, little known.

Scien

Foreword

We divide the history of the organ by convention into four eras: ancient epoch to 476 A.D. (fall of the Western Roman Empire); medieval epoch to 1492 (discovery of America); modern epoch to 1791 (year of W. A. Mozart’s death); and contemporary epoch to the present.

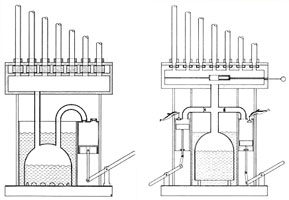

za ed Alimentazione

Let us preface this by saying that the chronological delimitation of a historical period is always an arbitrary thing, because every manifestation of thought proceeds without boundaries of time. The framing is related to the strand of the Italian organ, as from the classical period, that is, from 1500 onward, the organ took on various connotations depending on the territories over which it developed. We do not cite the names of the protagonists but give outlines of thought, in order to emphasize the dynamics of life and ideas that nurtured this singular aspect of human ingenuity: organ art. We will delve into the periods close to us, in order to enhance the organ heritage of the diocese of Guastalla, especially that of the famous Serassi.

Noteworthy in this classification are : the Ancient Ages and the Contemporary Ages.

Yes, these two periods are interesting, because as never before the function of the pipe organ was, not only as a musical instrument but, also, as a political and religious instrument. We will deal, in particular, precisely with the Contemporary Era.

THE CONTEMPORARY EPOCH

In the nineteenth century, a new style called resurgent-romantic emerged, the result of complex dynamics including popular, melodramatic-sentimental, political-religious.

(a) Risorgimento ideals. For much of the 19th century, roughly until 1870, a special situation occurs: the organ, now present even in small towns, becomes a means of spreading the military, social and political ideals proper to the Risorgimento. Patriotic motifs are played. The well-known organist Father Davide da Bergamo (1791-1863), born Felice Moretti of Zanica, in the Sinfonia with the much applauded popular hymn, treats, not without a hint of irony, the Hymn of the Austro-Hungarian Empire: “God preserve Ferdinand, save our Imperator”; the same in the pages The bloody days of March i.e., the Revolution of Milan, involves as in film sequences. The Risorgimento ideals not only influence the organist’s thematic choices, but also force the organist to immerse himself in popular culture, invent new sonorities, and build organs more and more in keeping with patriotic taste. Such a climate is fully understandable in the broad cultural movement known as Romanticism, which characterized the first half of the 19th century and brought about not only a real revolution in musical culture, but also accelerated the rejuvenation of formal classicism, typical of the Renaissance. There are two types of Romanticism: political and intimist. In the political one, the values of nation, art, religiosity and popular culture assert themselves; in the intimistic one, the values of subjectivism, of the conflict between the self and the world, assert themselves. In ours, the political one prevails.

(b) Popularity and modernity of organ art It is necessary to point out three basic concepts of Romantic art that characterize organ art: spontaneity, popularity, and nationality. According to spontaneity, form and content of each artistic creation arise together naturally and cannot be distinguished separately. For popularity, the artistic work must be addressed to the people and not remain closed within narrow academic circles. As for nationality, finally, it is necessary for art to express the interests and passions of the nascent European nations, particularly that of Italy. Organ art makes these themes its own and expresses them to the best of its ability: the organ becomes an instrument of expression of the everyday, of lived experience; in this dimension the people is not only the reference par excellence from which to draw inspiration, but the recipient with whom to deal, to whom to address the artistic message. The organ builder becomes the interpreter of these aspirations, which he translates into admirable machines. It is said, for example, that in Piacenza the aforementioned organist Father Davide, famous for his Christmas Pastorals, would make the pipers of the Apennines play for hours, and to imitate their nasal sounds he would put tow in the organ pipes. So the playing of the bagpipers’ carols, the Martials of the bands, the Preludes, the Arias, the Symphonies of the operas, is indicative not only of modernity but of civic consciousness, of social commitment. No art object is so present and alive in the everyday as the organ because by lowering itself into the popular environment it takes on its languages. Undoubtedly there are excesses: just as the precept of spontaneity produces exuberance of feeling and the fantastic, so that of popularity produces overabundance of superficiality. Making a comparison with the classical language of previous centuries, we can say, broadly speaking, that: in the seventeenth century, organ voices descended on the audience in cultured language, creating suggestions of admiration; in the nineteenth century, on the other hand, they confront the everyday. This beneficial osmosis between art and the everyday ends at the end of the century when the new languages return to being academic forms, detached from the popular.

(c) The religious in organ music It comes naturally to ask what was the relationship between the organ, a machine extraordinarily rich in sound and mechanisms, so much so that it is called an orchestra, and its liturgical purpose. Here are some considerations. The nineteenth century is dedicated to the splendor of melodrama; it is no wonder that manifestations of worship, addressed to God and the saints, are heard in such a martial and popular way according to the melodramatic style. From the organ music emerge the most characteristic traits of the religiosity of the time such as: hope, open trust in Providence, adherence to God’s plan, freedom of action, sentimental participation, and boisterous joy of Baroque heritage; those musics, therefore, are a fine example of freedom of expression of worship, great historical intelligence of Catholicism. In that context, what musical form is better suited for the liturgy than melodrama, which is performed, amplified and emotional stage action? Liturgical music is increasingly elaborate in orchestration: instrumental strength and timbral variety are required. Nineteenth-century organ-making not only increases the structure and power of the classical sound architecture of the Ripieno’s timbre, but is enriched with numerous colors with reed registers, many already present in the Baroque-type organ: Clarones, Oboes, Serpentones, Harpones, Military Trumpets, Violoncellos, English Horns, Bassoons, Choral Voices, Bombards, Trombones, Accordion; with the soul registers: Flutts, Fluttons, Horns, Octaves, Flagiolets, Sesquialtera, Cornets, Violins, Violones, Timpani, Contrabasses; with percussion registers: Bells, Bells, Gran cassa, Cymbals, Rolling, Drum, Bufera, and others.

Cybernetics, Technology, Symbol of power Politics, Instrument that brings man closer to God.

From what we read above we realize how many purposes a single musical instrument can have on entire Peoples. Perhaps, the first imitation of Nature, of its becoming in sound, of how man with his mind could have rewritten rules of which he knew only the conclusive part: the sound of birds, of weapons in battle, of water in a stream, of footsteps in a clearing; reproduced with the individual pipes of this wonderful pipe organ.

At first a tool for a few rich and oligarchs, later, accessible in any small church even in remote and almost deserted villages.

Music for nobles, but, used to control and gherminate the poorest. Fuel to inflame Peoples against other Peoples ; call back to "patriotism" millions of soldiers and awaken love for that flag, also, created only a few years earlier.

I don't know about you, but, this duality Religion and War has always fascinated me in the function made of the pipe organ and it must make us think about how technology, in general, is always affected by the kind of path that man himself decides to make his creations take.

Address: via Ammiraglio Millo 9 .

Alberobello, Bari. ( Italy )

📞 +39 339 5856822