Maino de’ Maineri’s Regimen Sanitatis dates from the early 14th century and is part of a late medieval treatise, heir to the Greco-Latin and Arabic traditions, oriented toward the maintenance of health. In it, prescriptions of hygiene and dietary rules, in addition to providing instructions of a practical nature, respond to an idea of “right measure” related to the nature of food and its nutritional function.

The principles on which medieval dietetics rests turn out to be already defined in the theory of the four humors elaborated by Hippocrates of Cos in the late fifth century B.C.E. and systematized by Galen of Pergamum in the second century A.D.1 Galen added to the Hippocratic theory the concept of “temperament” and elaborated the categories of “res naturales” and “res non naturales”,which later became the canonical structuring of medieval regimina sanitatis.

According to this canonization, “res naturales” are the constituents without which the organism cannot subsist, namely the “four elements” (air, water, fire, earth), the qualities or oppositional pairs hot/cold, dry/hum ido, the four “humors” phlegm, yellow bile, black bile, blood, the parts, faculties, operations, and “spirits.” The “res non naturales” are those external factors that influence the humoral balance of the organism, favoring or warding off disease aggression (“things against nature”) depending on circumstances and other subjective variables such as age, profession, “temperament,” sex.

The “res non naturales” essentially concern six areas: aer (air/environment); cibus et potus (food/drink); motus et quies (exercise/rest); somnus et vigilia (sleep/wake); repletio et evacuatio (expulsion or retention of “humors”); accidentes animae (affections of the soul, passions, or psychological states). Regarding the binomial cibus et potus (as with the other “res non naturales”), one of the cornerstone principles of ancient and later medieval medical knowledge applies, namely the concept of balance between the opposing qualities of the elements.

The recipes of Maino de’ Maineri’s Regimen reflect this concept in the idea of a “proper mixing” of the properties of individual foods, in relation to the “moods,” “temperaments” of man, as well as to the seasons and cosmic elements. This is a system of balances that invests both the medicinal and culinary spheres; in this sense, there has been talk of a “galenic cook” and “dietetic cuisine

Life and works of a physician in the service of the powerful

Maino de’ Maineri (also called Magnino) was born in Milan to Giacomo de’ Maineri probably between 1290 and 1295; a scholar, man of the court, knight, physician and astrologer, he came from a noble family that took part in Milanese life at the time of the struggle between the Communes and the Empire (12th century). From a Maynero comes the branch of the family living in Mozzate on the Comasco (the “old stock” from which Mayno comes), rich in fiefs and allodial possessions, as well as in the Comasco, Piedmont, and Lodigiano. Magnino spent his youth in Milan under the rule of Guido Torriani, from whom the Maineri received benevolence and protection. In 1326 he is a professor at the Faculty of Medicine in Paris. His protector and overlord is the Florentine nobleman Andrea Ghini de Malpighi, following whom the Milanese physician travels to France. Five years later (1331), though married, Magnino obtained permission from Pope John XXII to continue teaching at the medical school in Paris, despite the fact that celibacy was imposed as a rule on all members of the Faculty. Later, he followed the Florentine prelate to Tournai (1334-1342); at this time he may still be teaching medicine at the Parisian faculty. In 1346 Magnino is in Milan, registered as the Visconti’s physician and astronomer; the following year he accompanies Isabella Fieschi, wife of Luchino Visconti (lord of the city), on a trip to Venice. He is still alive in 1364; he dies probably not many years later.

A cook … a scientist

Beyond the scant biographical information, it is mainly Maino de’ Maineri’s works that bear witness to his activities as a physician and intellectual in Milan and Paris. They concern diverse areas of science: medicine, dietetics, astronomy.

The best known writing is the Regimen Sanitatis, a manual of practical advice for leading a healthy life dedicated to the aforementioned Andrea Ghini de Malpighi, bishop of Arras from 1331 to 1333 (the same years, probably, of the composition of the treatise). In the following centuries, the Regimen experienced considerable diffusion, testifying to a genre of treatises that had become widely consumed in the late medieval and modern ages; especially, it was the art of typography that favored its wide circulation and spread the author’s fame.

There are numerous editions of the Regimen dating from the late 15th and early 16th centuries that bear Magninus’ name at the beginning and end of the work. The first known is printed in Louvain in 1482; a second, also in Louvain in 1486. Other editions followed: one published in Basel in 1493, another in Paris in 1498. Again, publications dating from the early 16th century are known: one in Basel and one in Strasbourg in 1503; another made in Lyon in 1517, followed by two more in 1520 and 1532 also in the same city; finally, an edition produced in Basel in 1590. In such prints, the author’s name is accompanied by epithets of praise, such as “most expert physician,” or “most famous physician”

There is, however, one edition of the treatise that brought Magnino a heavy accusation of plagiarism. It is the version of the Regimen that appeared in the Works of Arnaldo da Villanova, a Spanish physician who lived in the second half of the 13th and early 14th centuries, published in Lyon in 1504 by the Genoese Tommaso Murchi. The title page of that version bears the inscription: Incipit liber de regimine sanitatis Arnaldi de villanova quem Magninus mediolanensis sibi appropriavit addendo et immutando nonnulla. Probably, according to Pius Rajna, it was Murchi himself who made the accusation, which remained in later editions without, however, the name of the accuser. Hence the generation of two distinct traditions, one attributing the work to Magnino, the other believing it to be by Arnaldo di Villanova. According to Rajna, the Lyon edition of 1504, which is shorter than the manuscript version of the Regimen in his possession, is possibly a redaction made by a physician who had transcribed parts of Magninus’ work for his own use. Several studies are, still, underway to estimate its plagiarism or not.

“Anti-Epidemic Recipes ”

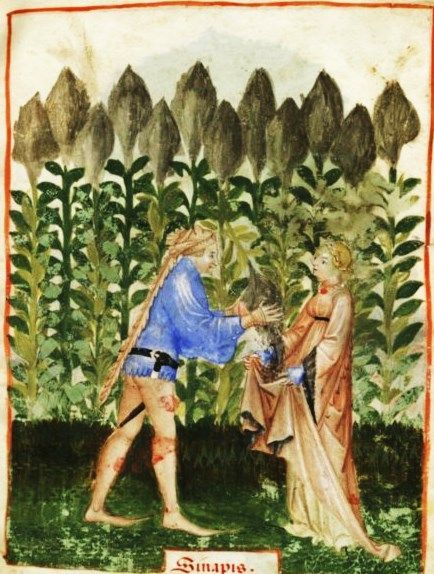

Miniature of a recipe from the 1200s

In 1360 Magnino also drafted the Libellus de preservatone ab epydemia, probably as a result of the plague of 1348; again, the Liber medicinalis octo tractatuum dates from the years when the author was in the service of the Visconti family (after 1346). In addition to his medical interest Magnino cultivated other areas of science, such as astrology and palmistry. Evidence of this is the Theorica corporum celestium (1358), the Livre de cyromancie (which has come down to us in French), a work of philosophy, De intentionibus secundis (written in the years 1329-30), and a treatise on morals, the Contemptus sublimitatis.

Address : via Ammiraglio Millo 9 .

Alberobello, Bari. ( Italy )

📞 +39 339 5856822