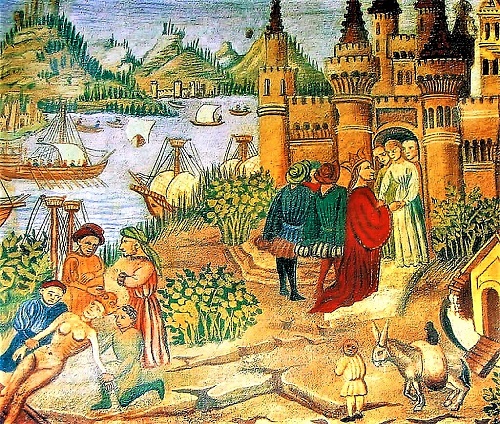

In these two contributions we have highlighted Maineri’s scientific approach to dissecting and dosing each ingredient, with a dedication more akin to the Galilean scientific method than the alchemical. We continue, now, to deal with other recipes and raw materials that lead us, directly, to the Middle Ages

Meat and Fish

A same formulation of dietary regulations attentive to the nature of the ingredients and their preparation concerns more complex prescriptions, which require not only the cooking of the meat and the pairing of it with a sauce, but presuppose a precise processing of the food. And this is the case with “pastillatura,” a preparation by which meat is encased in a thin flour mixture, which involves cooking comparable to today’s baking, apt to moderate the “moisture” of the meat, although to a lesser extent than roasting.

Magnino recommends preparing this “batter” with beef and pork together, and seasoning it with sweet spices (very “hot” and “dry”), agresto, “butiroso” cheese in summer; in winter with white onion, strong spice powder, and agresto. Or, he suggests a “pastillatura” ex carnis subtilioribus: in that case, the recipe calls for a “pastilla” of “thin” meats, with almond milk, agresto, sweet spice powder, and egg with agresto, for the summer season; wine and more spices in addition, in winter. These are perhaps dishes that originated in northern Italy, or were commonly consumed there in the Middle Ages. Another sauce of note in the Milanese doctor’s cookbook is camelina sauce, consisting of ginger and cinnamon, mentioned mainly in French-area cookbooks.

In the Regimen it is recommended in combination with roasting rabbit and chicken and is composed of water and cinnamon; it can be made thicker by adding bread crumbs, with agresto in summer and wine in winter. It is a “hot” and “dry” sauce, cinnamon (its main ingredient) being “hot” and “dry” to the third degree.

Among other birds, three recipes are reserved for capon (castrated rooster when young) and chickens. One of them calls for boiling as cooking, which is suitable for preserving the “hot” and “moist” nature of these meats. According to this recipe, the seasoning involves as the liquid-base the water (“hot” and “moist”) of the meat itself, with the addition of more water, all mixed with crocus and vine juice in summer; or, with sweet (“hot” and “dry”) spice powder, sage, hyssop, parsley, in winter. Otherwise, if you make a “pastillatura” (i.e., meat enclosed in a thin mixture) of capon and hen both fatty, it is good to season it simply with a little spice powder, to which you should add agresto in summer, wine in winter.A winter sauce, to be used with roast capon and hen, is Valba allea bullita; or, a wine-based seasoning with good spice powder, especially sweet wine, may be sufficient. In summer Magnino suggests using “weak” (clear) wine or agresto, with less spice powder than used in winter.

These recipes reveal the constant attention to the “right flavor” sought by the author for each food item and responds to the belief that dietary needs and gastronomic pleasure are essential in the dietary diet. This is a “lean” cuisine, typical of medieval times in which fats, such as oil and butter, do not appear in the composition of sauces, which generally consist of wine in winter, vinegar in summer and winter, and agresto in summer.

To these elements are added herbs or spices, including, for example, ginger, saffron, pepper, parsley. Often, to make the sauce thicker, Magnino suggests the use of roasted bread, almonds, egg yolk; conversely, he recommends the use of meat stock, to make it more dilute

Un cuoco … uno scienziato

Fish sauces and seasonings

Since Antiquity, the attention accorded to fish in encyclopedic-naturalistic works also invests their therapeutic virtues: think of Pliny’s Naturalis Historia or Solinus’ Collectanea rerum memorabilium.

This heritage of notions is transmitted to the early Middle Ages through the mediation of authors such as Isidore of Seville (mid-6th-mid 7th century) and Rabanus Maurus (late 8th-early 9th century), who in their treatises supplement ancient knowledge with passages inspired by sacred Scripture and the holy Fathers. In the more purely dietary-culinary sphere, the Greek physician Antimo (6th century) devotes several paragraphs of his epistle De observatione ciborum to listing the types of fish considered “good” in a proper diet; of them the author indicates the most suitable seasonings and cooking depending on the quality of the fish connected to the original habitat of the animal (sea, river, pond, etc.). In the 12th century, Hildegard of Bingen illustrates in the fifth book of her Physica the variety of fish known to her, classifies their quality according to their environment of origin, and describes their therapeutic properties. These are opinions connected “to a solid tradition, into which Greek-Arabic notions had converged during the 11th century, through the mediation of Constantine Africanus.” Such medico-naturalistic notions are found in the medieval regimina sanitatis especially with regard to curative aspects.

In Maino de’ Maineri’s treatise, fish dishes are of no small importance, so much so that within Chapter XX concerning sauces and condiments an entire paragraph is devoted to sauces to accompany fish: De saporibus et condimentis piscium. The types of fish mentioned by the author come from marine and river environments. His focus is mainly on the different quality found in freshwater and marine fish, the latter better than the former because their flesh is less laden with “superfluity,” less “phlegmatic,” and closer to nature than that of quadrupeds. Compared to freshwater fish, marine ones are more difficult to digest. For both it is necessary to choose fresh ones, whose flesh “non est viscosa sed frangibilis, non multum grossa sed subtilis, non gravis odoris sed suavis.” Another factor that should not be overlooked is the hygiene of the places where the fish come from; those that inhabit lakes, ponds, sordid waters are to be avoided; the optimal habitat is deep seas, characterized by continuous water exchange, into which many tributaries flow. Entirely inadvisable are fish that live in dead, southern seas, which are less rough than northern ones and therefore less healthy. In addition to their place of origin, the intrinsic qualities of these animals are crucial. Often, their “wet” and “cold” nature requires the use of “hot” and “dry” sauces, and how much “sunt grossioris carnis et difficilioris digestionis et plurium superfluitatum et humidioris nature tantum indigent saporibus calidioribus et acutioribus.” This rule applies especially to “bestial” fish because of the “coarseness” (excess fat) of their flesh. Among them, for example, porcus marinus requires the use of piperata nigra bullita, a sauce whose ingredients are of a very “hot” and “dry” nature: black pepper, cloves, roasted bread soaked in vinegar, all diluted in the broth of the fish itself.

The essential function of such a broth is, due to its “moist” nature, to temper the “dryness” of pepper and cloves. Compared to the piperata suggested for meat, piperata nigra bullita is stronger and “sharper” due to the presence of cloves (not provided for meat), which are suitable for limiting the excess “wetness” and “cold” nature of porcus marinus. The eel, moray eel and lamprey, similar in nature to that of the porcus marinus, “requirunt pro sapore galentinam ex fortibus speciebus,” a mixture of three very “hot” and “dry” spices, cinnamon, galanga and cloves, together with wine and the broth (hot, tempered in “moisture”) in which the fish is cooked. It is a sauce to be consumed cold a few days after its preparation, or to be used for preserving fish.

Sometimes, eel and moray eel (but also congro) are roasted, and then “sapor conveniens est salsa viridis cum fortibus speciebus et vino in hyeme et cum debilibus speciebus et agresta et vinegar in summer. “106 As in the case of meats, salsa verde is composed of parsley, rosemary, roasted bread, white ginger, eggs, and cloves. The function of this sauce, like the others, is to make the fish “hotter” and “drier” than it is in its natural state. Regarding red mullet and capon fish, considered the best among saltwater fish, Magninus prescribes two simple and light sauces, the use of which depends on the type of cooking: if boiling is chosen, it is good to use camelina sauce, moderately “hot” and “dry,” made with vinegar and cinnamon, with agresto in summer; temperate wine, in winter.108 Otherwise, roasting and frying involve the use of salsa verde, in winter with vinegar, wine and spices; in summer a milder flavor with agresto and vinegar is suggested. Or, with roasting the author recommends a sauce used in the French area (“apud gallicos usitata”), which is not excessively “dry”: it consists of white ginger, diluted in wine, with which, in turn, the roasted fish is moistened. Such preparation is suitable for winter; for summer, in place of wine, it is best to use agresto and, in smaller quantities, ginger. Green sauce is also suitable for frying small freshwater fish, which are generally less “cold” and “dry” than the others; if boiled in water, a dressing of mustard or eruca and white onion cooked with the same is appropriate. Regarding pike and barbel, their boiling requires the use of salsa verde; frying and roasting require the use of wine or agresto, as a liquid-base, in which to dilute boiled white ginger. This is served over cooked fish (roasted or fried) and serves to moisten them ” What is good is good for the health” Magninus’ Regimen Sanitatis is part of a late medieval treatise rooted in ancient medicine.

A fundamental assumption of this science is the idea that each person should eat according to his or her physiological characteristics, that is, according to his or her “humoral complexion,” age and sex. Of no less importance are external factors such as climate, natural habitat and standard of living, which affect the individual’s health status and quality of life. While in ancient manuals the set of these elements relates to man tout court (devoid of any particular meaning), by the time Magninus writes (1930s) the act of eating according to the “quality of the person” has taken on social and cultural significance. To each class, in accordance with its position in the social hierarchy, corresponds a particular food. The more the individual belongs to a high rank, the more refined the food he or she eats must be; the more the individual belongs to the lower strata of society, the more suitable coarse and common food is. Such a hierarchy of foods is not present in Maino de’ Maineri who, in accordance with the conception of the ancients, distinguishes groups of individuals according to their “humoral complexion,” age, season, and ability to interact with the environment. Perhaps some of these recipes are the result of the author’s personal observation, such as certain usages that Magnino refers to as French (“apud gallicos usitati”), which is the case of the sauce combined with mullet and capon. For other recipes, too, there are references to common practices in certain geographical areas. For example, camelina sauce (composed of ginger and cinnamon), often mentioned in the Regimen, is widespread in the French area, as the recurrences of this sauce in French cookbooks coeval with the work of the Milanese physician suggest.

Again, the use of “pastella” or “pastillatura” as a pastry casing that covers the meat seems to be a custom in vogue during the same centuries in northern Italy. So, these are recipes that in most cases refer to two well-defined geographical areas, Paris and the kingdom of France on the one hand, Milan and Lombardy on the other. The “experimental” character of the Regimen is not only related to the author’s desire to prefer concrete rather than theoretical aspects. The intervention on food also, and above all, refers back to hygienic concerns, of Hippocratic derivation, according to which no food in nature is balanced and the health of the individual depends on the ability to construct a balanced diet.

Manipulating and preparing foods so that they ensure the maintenance of health, or at least do not damage it, and are at the same time pleasing to the taste are primary needs in the conception of the “doctor-cook” Maino de’ Maineri. In this sense, gastronomy and dietetics are two complementary aspects of the same knowledge related to the principle that “what is good is good for your health.” These are widely shared rules in the dietetic treatises and cookbooks of the late Middle Ages, characterized by the same language that records the experience of the sensory world and subdivides foods into the sensory categories hot/cold, dry/wet. It was not until the 17th-18th centuries that dietetic science and gastronomic art began to distinguish themselves sharply, the former using a new language based no longer on physical observation but on chemical analysis. In the works of the Milanese physician, the recipes that most embody the idea of a science of healthy living, conceived in its two fundamental aspects, the art of cooking and medical knowledge, are those related to sauces. If in the Opusculum de saporibus they appear with a mainly corrective function for foods, in the Regimen this function is, more decisively, juxtaposed with the culinary one.

Intervention in foods does not respond to a reductive value of “diet” as it is commonly understood today; as in the ancient tradition, a broader notion of the term remains in the medieval tradition. However, if in classical dietetics the term diaeta was identified with a regimen of life, including nutrition, physical (and intellectual) activity and bodily hygiene, in the medieval treatises considerable space (among the “res non naturales”) is accorded to diet as a privileged tool for the purposes of maintaining or restoring health. In the Regimen of Maino de’ Maineri, as in many regiminas of the 13th-14th centuries, the meaning of diaeta narrows in favor of cibus et potus (at the expense of the other “res non naturales”) falling within the scope of the “construction of a gastronomic culture” proper to that medieval universalism that invests both cuisine and dietetics

We look forward to the next article !!!

via Ammiraglio Millo 9 ( Italy)

Alberobello, Bari.

📞 +39 339 5856822