The pipe organ has always been considered an instrument relegated to the Catholic Churches for the Catholic Churches, in reality, the dignity and history of this instrument are much deeper and more interesting.

Its importance in the literary, archaeological and figurative fields shows an instrument with precise political and diplomatic features, such that it is a sound image of the imperial power of Ancient Rome.

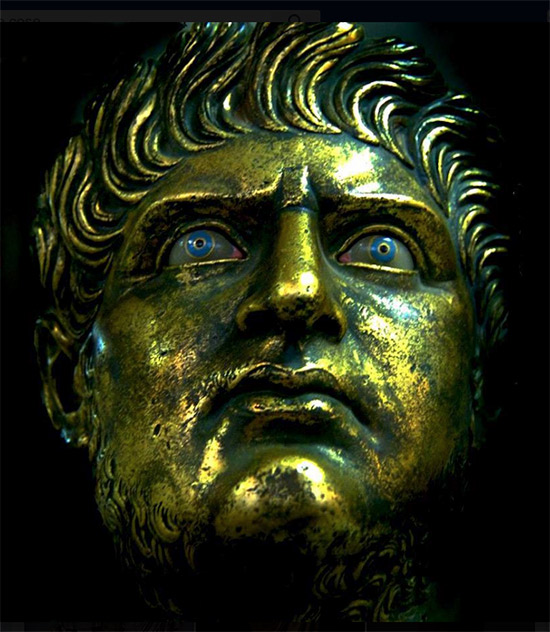

As with all the stories you don’t expect, this article will discuss one of the most famous and discussed Roman Emperors, Nero. Historical Sources on this particular story have been handed down to us by Suetonius and Vitruvius, with two completely different political views.

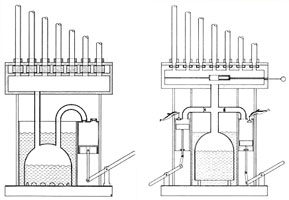

The contribution starts from the choice of Vitruvius, an engineer of the early Augustus, to include in De Architectura the instrument as a complex machine, useful in peacetime to express the image of the glory and power of the emperor who was able to build it.

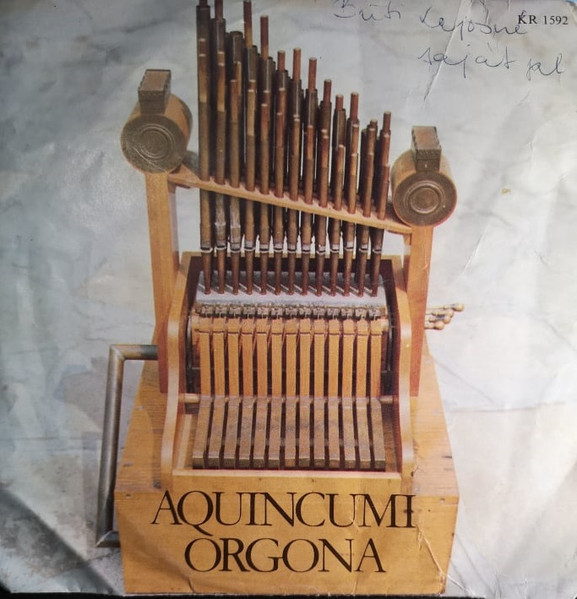

It goes on, then, referring to the presence of the instrument during Nero’s empire and proposing the hypothesis of the existence of an instrument of its own in the emperor’s private palace. Through the rereading of some passages from Suetonius’ Vita Neronis and some archaeological findings unearthed in the Domus Aurea on the Esquiline, a new interpretation of Nero’s life, especially musical, is proposed.

Scien

NERON AND HELLENISM

Nero, like the members of the Ptolemy family, was educated by figures of ‘special’ character such as a dancer and a barber (recall that, according to the Vitruvian and Athenaeus of Naucrats tradition, Ctesibius himself was the son of a barber or barber himself).Nero’s penchant for music, theater, and spectacles grew with him and reached its highest expression when he became emperor. Like the Hellenistic kings, he knew that the glory of his empire in peacetime was also demonstrated through the greatness of spectacles.

za ed Alimentazione

His contacts with the Hellenistic world are captured in the relations he established with the Alexandrians. An important number of his collaborators, in fact, were of Alexandrian origin, such as T. Claudius Balbilus, the prefect sent to Egypt at the beginning of the Neronian Empire, who was in charge of the museum and library.

There is evidence concerning the organ in the Roman Empire during the reign of Nero. The path, literary and archaeological, shows an instrument with precise political and diplomatic features, such that it became a sonorous image of imperial power. Thus the instrument had already been outlined since its invention at the hands of Ctesibius, an engineer in the court of Ptolemy II Philadelphus. The relationship between Ctesibius and Ptolemy, in fact, appears in summary as the relationship that has taken place between a technites and a technocrat, or rather between a technites who proposes to his commissioning technocrat machines for good government.

This relationship seems to recur, in the Roman environment, with Vitruvius and the dedicatee of his work: the emperor Augustus.

In this ‘political perspective’-that is, organ as an artifact linked to logics of power valid in peacetime, the presence of the instrument even during the reign of Nero (54-68 CE) should be reread.

Nero man of Art … much less man of Politics

In Suetonius’ Lives of the Caesars, we read that the young emperor had been greatly fascinated by Eastern culture and had especially appreciated the sensitivity to art and the competitive spirit that characterized the agons, true examples of culture. However, Nero’s involvement is total and, for Suetonius, negative: the emperor is so involved that he forgets his public duties. Thus when in Naples, in March ’68, he received news of the insurrection of the Gauls, led by Julius Vìndice legate of the Lugdunan colony, he “disturbed during dinner by an alarming letter, limited his anger to threatening all evil to those who had rebelled.”

This is to testify both to the existence of this “instrument of the highest musical technology” and to his displeasure no for the rebellion of the colony, but, for the delay in the development of the hydraulic organ.

Nero’s attitude is reminiscent of the confidence that Hellenistic kings placed in knowledge: in his apparent folly, he seems convinced that he will be able to keep his reign stable through the demonstration of knowledge and technological know-how.

Where could Nero’s Hydraulis have been located?

The palatial complex of the Domus Aurea covered an area of as much as 80 hectares and occupied the heart of the city, extending, with ideological intent, over one of the most sacred sites of Romanity: the ancient Septimontium. The part of the architectural complex of interest here is that located on the Esquiline pavilion, a sector of the Domus reserved for the emperor’s otium, with functions of representation and propaganda.

The structure can be divided into two parts: the western one, with a traditional architectural layout, appears to have been reserved for the emperor, while the eastern area, with an innovative structure, appears to have been intended for representation. The latter was characterized by the presence of an octagonal hall, which today is considered the hub around which the rest of the palace wing was developed in a radial pattern.

It is possible, then, that Nero’s engineers, who had equipped the Esquiline Palace with some Ctesibian hydraulic apparatus, had not overlooked the hydraulic organ either, described by the contemporary Alexandrian mechanic transplanted to Rome: Heron.

When Nero called the senators “to his house” to show them a new kind of hydraulic organ, it is likely that he brought them to the very eastern part of the palace on the Esquiline. This would perhaps have been the ideal place: it was a private but equally representative palace. Nero, moreover, seems to have been the only one who knew of the instrument (or, at least, it was still an unknown model that he would soon bring to the theater to show to the large audience); the instrument therefore could not have been in the Palatium on the Palatine, the political center par excellence habitually frequented by senators and all Roman patricians.

The organum novi generis, which Nero wished to show his men, could therefore have been in the eastern part of the private palace: if not precisely in the octagonal hall, destined for the most sumptuous banquets, or in those definable as alcove rooms, the instrument could have been in a room near and antechamber to those rooms, such as the Nymphaeum, a room linked to the cult of water and made more striking by the presence of another hydraulic device: the waterfall fed with water from the Esquiline.

Suetonius and his “barbs” at Nero.

Unfortunately, our main source, the Swetonian Life, does not help us further to support the hypothesis about this precipitous location. Although Nero and the intellectuals of the time-such as Heron, Pliny, and Seneca-had retained the traits of 'mechanical' Ptolemaic politics, something in the process of transmitting technocratic politics from Nero's Roman world to the Swetonian world had changed. Evidently the Roman culture of the Suetonian period had removed the memory of the Hellenistic conception of power understood as knowledge and technological superiority applied to different fields of knowledge. Suetonius' generation perhaps lacked a figure.

Times had changed and with them the magic of Hellenistic technocratic culture..

Address: via Ammiraglio Millo 9 .

Alberobello, Bari. ( Italy )

📞 +39 339 5856822