The simple method…

Just like for i dry tomatoes, even dried figs are prepared simply using what nature offers us for free: the sun. You don't need who knows what equipment but it is important to have fresh, healthy and ripe figs at the right point so that, drying in the sun, they dry just right without becoming crunchy but still keeping a certain amount of pulp inside.

Obviously the fact that they have to be dried under the sun implies that the timing is not exactly fasti: it is in fact necessary that the figs are always exposed to high temperatures for which they must be kept under control, so that when the sun starts to turn and change position, the figs are also moved and their position is changed.

This procedure, which has been used for centuries in the families of Southern Italy, has been scientifically studied.

Yes, you got it right, there is more than one scientific article describing a lot of laboratory tests and methodologies what could be the best way to create dried figs. In your opinion, could we at AILoveTourism avoid being analytical and "strange" as usual?

ENJOY THE READING. Article by CM. PAPOFF -G. BATIACON -M. AGABBIO -G. MllElLA – F. GAMBElLA -A. VODRET – University of Sassari 1997

PREMISE

It refers to a drying test by dehumidification of fig fruits (Ficus carica L.) of the cv "Niedda longa". The fruits, separated into two batches differing in weight, were dried for 120 h (A) or 96 h (B), with a dehumidifier, weighing 29 kg, which maintained the temperature and relative humidity values of an environment of 8.5 m3, respectively between 30.5°- 32.0°C and 34-400/0. Lots A and B respectively, at the end of drying, had a dry substance content of 79.3 ± 0.88% and 69.6 ± 4.740/0. Finally, the fruits were treated with potassium sorbate, also packaged in a modified atmosphere regime and stored for 3 months at 20°e. Lot A was the closest, in chemical composition, to imported dried figs. However, as far as the counts of yeasts, molds and epiphytic bacteria are concerned, both batches showed no notable differences compared to the imported figs. Therefore, it seems that the combination of dehumidification and treatment with potassium sorbate makes it possible to produce dried figs stable over time.

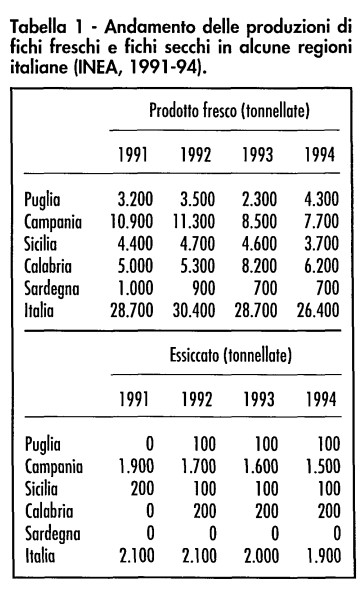

The cultivation of the fig (Ficus carica L.), despite being one of the oldest in the whole Mediterranean basin, is now economically important only in some countries of its eastern area. Lastly, specialized cultivation is spreading in Italy, leading to the expectation of a greater interest of the agricultural sector in this fruit production. The fruits (sycones) are marketed fresh or dried. Post-harvest conditioning and transport technologies (refrigeration, use of controlled and modified atmosphere, packaging in plastic films), even if they allow the product to be sent to more distant markets, have a high cost/post-harvest life extension ratio, particularly when compared with those of other fruit species. Italy is, in any case, one of the major exporters of fresh fruit, in particular with a moderate economic value for Puglia, Calabria, Sicily and Campania (tab. 1, from INEA 1991-94). Conversely, Italy satisfies its consumption of dried figs basically with imports, in particular from Turkey and Greece. Among the cultivars used for drying, in Italy the best known is the “Dottato” (Addeo et al., 1991), while among the foreign ones the most widespread is the Turkish “Smyrna” (or “Lob Injir”), from which derives the “Calimyrna”, a cultivar used in California.

In general, dried figs are produced from varieties with light colored (white) fruit, even if there are productions from cultivars with dark (black) fruit such as, for example, the Americana (of Spanish origin) "Mission" (Cruess , 1958). The most widespread drying is that for direct exposure of the fruit to the sun (natural drying), where the syconia are placed on supports (racks) of various materials, continuously moved by hand, in order to favor both a uniform dehydration of the fruit and The acquisition of a shape suitable for packaging. This technology has undoubted disadvantages such as the impossibility of controlling the atmospheric conditions, the significant use of manpower, the precarious hygienic conditions in which all the phases of the process take place, with consequent high losses due to attacks by microorganisms and insects. The use of mechanical means of protection cannot effectively limit the incidence of this type of damage. It is therefore necessary to resort to anti-mould or anti-insect products (such as, for example, sulfur dioxide), often in high doses, which can negatively affect the healthiness of the finished product. The industrial drying of figs appears, for the moment, to be difficult to implement in those areas of Southern Italy, where the small production dimensions characterize the average farms. Furthermore, the needs of an industrial structure, which requires regular supplies of standardized fresh product, cannot be reconciled with the capacity of these companies, which offer discontinuous productions in quantity and heterogeneous in terms of fruit ripening characteristics. Therefore, in the short and medium term, it is believed that other drying techniques could be useful, which allow a valid alternative to the natural process in the sun and which, at the same time, require financial investments that are also accessible for farms interested in the production of limited quantities of figs dry. (with the present experience we wanted to verify the effect of drying by dehumidification on the characteristics of the main qualitative parameters of the fruits of a variety of figs of the Sardinian germplasm.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The syconia used in this trial were of the “Niedda longa” cultivar, a variety producing bifera (the fioroni in July and the figs from the 3rd week of August). This is the most widespread variety in Sardinia, characterized by the purplish-blue color of the fruit skin. When ripe, syconia have a high percentage of total soluble solids in the juice, a characteristic which makes them susceptible to industrial processing. Processing technology The chemical-physical principle that we wanted to exploit, to carry out the dehydration, is that of shifting the dynamic equilibrium that is created, in a closed environment, between the different humidity content of the fruit and that of the air. In this case the drying process provides for the transport, by environmental ventilation, of the water vapor from the surface of the fruit to the surrounding environment, to then be condensed with a dehumidifier. The exposure of fresh figs in an environment characterized by low relative humidity (UR), around 300/0, and by temperatures similar to summer ones, around 30° (, allows an optimal flow of water vapor from the fruit to the plant collection of humidity.This process, which is always governed by the latent heat of evaporation, can be represented as follows: the passage of water molecules from the liquid state (as moisture in the fruit) to that of vapor (in the air); – by continuously withdrawing water from the environment, saturation equilibrium is prevented from being reached. 996 Food Industries – XXXVI ( 1997) September The dehumidification test was carried out in a room (8.5 m3 ) without windows. Access was closed with a wooden door. The dehumidifier, not specifically designed for this purpose, had the following characteristics: alternating current at 220 V with maximum absorption of 1,590 W; maximum volume of treatable air 260 m3 /h; air humidity removal system by condensation with R22 refrigerant gas; air heating system with electrical resistances and regulation thermostat. The dimensions of the apparatus were: width 435 x depth 325 x height 580 mm; the weight was equal to 29 kg. The instrument was adjusted to 75% of its maximum power, both for dehumidification and for heating the air. Furthermore, an electric fan with timer was positioned next to it, in order to ensure the movement of the air, with ventilation cycles of 30 min/h. Throughout the test, the environmental parameters of temperature and relative humidity were measured with a thermo-hygrograph. The dehumidification scheme envisaged a careful selection of the fruits which, harvested in the third decade of September, were kept for 24 ha at 4°C, until the moment of processing. The fruits were calibrated in 2 batches of 10 kg each, composed of elements with an average weight equal to 35.8 ± 5.9 g (batch A) and 22.1 ± 5.6 g (batch 8). The fruits were subsequently scalded in hot water at 95°C for 2 min (blanching) and finally dehumidified for 120 h (A) and 96 h (8). At the end of the dehumidification, the fruits, exposed to the air for 24 hours, were treated by sprinkling for a few seconds with a solution of potassium sorbate at I2,5%, then sealed in airtight plastic containers, in packs of a maximum of 125 g of weight each. Half of the packages were saturated with a mixture of 02′ CO2 and Nr at 3.00, 0.35 and 96.65% respectively. The relative packages were identified as AN2 and 8N2, respectively from the two original lots A and B. Finally, all The bags were transferred at 20°(, in order to study the stability of the product in simulated storage conditions in the sales warehouses (shelf life)

Chemical analyses

During the dehumidification process, fruit samples were taken at the following times: 0 (after blanching), 4, 24,48, 72, 96 and 120 h, for the determination of the humidity content (AOAC 934.06, 1990). At the end of the blanching and before sprinkling with the potassium sorbate solution, the pH and lactic acidity were determined with the following procedure: 25 ml of distilled water were added to 1.5 g of fruit, the suspension was homogenized in Ultraturrax at 13,500 rpm for 10 seconds. Subsequently it was centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 10 min and on the supernatant, filtered on Whatman 41 paper, the pH was detected in sequence by potentiometry and, then, the acidity in lactic acid (mg/100 g) by titration up to pH 8.2 with NaOH 0.01 N. The analyzes were also completed with the determinations of the ash (Ministerial Decree of February 3, 1989) and of the total sulfur dioxide (AOAC 963.20, 1990). The data relating to the dry matter, ash, pH, it-lactic and sulfur content were statistically processed using a one-way ANOVA, considering the 2 lots A and B as "group variable" and using the 1st program MST AT -C ( Michigan State University).

Microbiological analysis

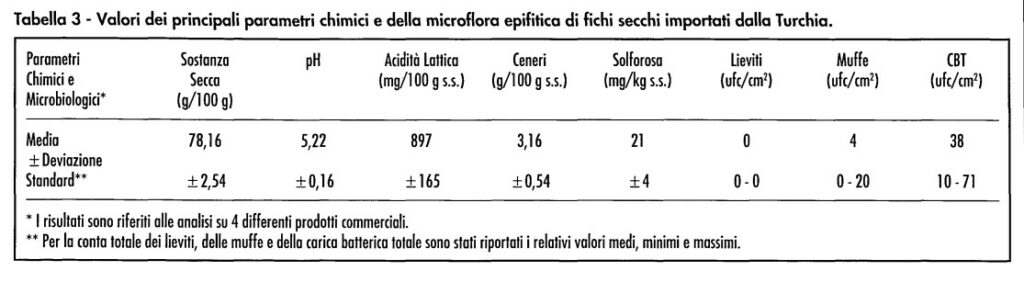

The analyzes were performed on the following samples: a) 7 fresh fruits (before separation into the 2 lots); b) 6 fruits at the time of packaging, of which 3 taken from lot A and 3 from lot B; c) 12 fruits taken from lots A and AN2, B and BN2 (3 for each lot) after three months of shelf life. 1 cm2 of epidermis, sterilely taken from each intact fruit, was subjected to stirring, in test tubes containing 5 ml of distilled and sterile H2 0, at 120 rpm for 2 h at 25°C. 1 ml was taken from the microbial suspension and inoculated in another 9 ml of distilled and sterile H2 0 in a test tube, in order to obtain a serial dilution, up to 10-5 • From these dilutions, a 0.5 ml aliquot was inoculated in GYEP plates (glucose 20/0, yeast extract O,5% and peptone 1 %) for yeast and mold counts and PCA plates (Oxoid, Unipath LTD, Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK) for bacterial count total (CBT). The incubation was 48 h at 25°C for the yeasts and molds and 48 h at 37°( for the determination of the CBT. Furthermore, for the purposes of an analytical comparison of the chemical and microbiological qualities, all the above analyzes were repeated on 4 commercial packs of dried figs, found directly on the retail market (all of Turkish origin).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

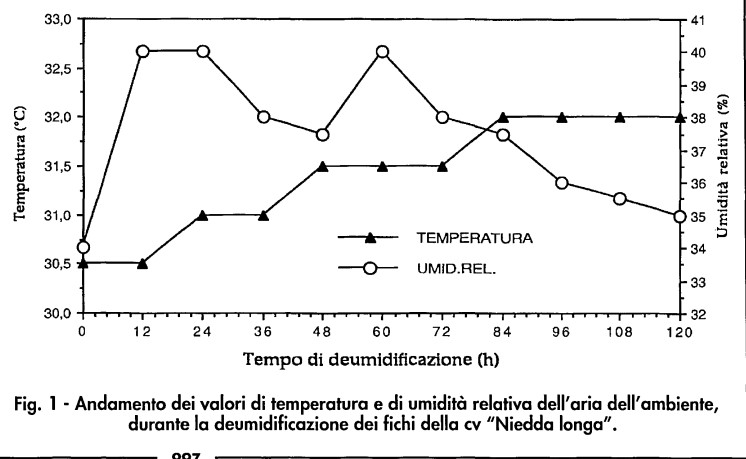

Dehumidification process The rate of temperature increase in the dehumidification room was 0.5°c/24h in the first two days, FRUTTA slowing down to 0.25°c/24h in the last part of drying (fig. 1 ), having reached the initially programmed value of 32°C. The decrease in the RH content showed a more irregular trend, strongly influenced, at the beginning of the test, by an increase due precisely to the introduction, into the room, of the mass of figs to be dried. The subsequent increase in RH of the air, around 60 h (fig. 1), was linked to the interruption of the functioning of the dehumidification system, due to the filling of the water collection container which, from that moment, regularly emptied, ensured the constant lowering of the value of this parameter down to the minimum de135% (fig. 1).

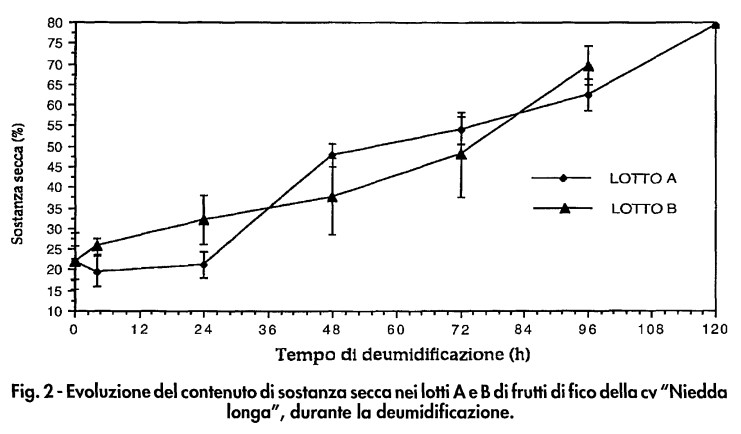

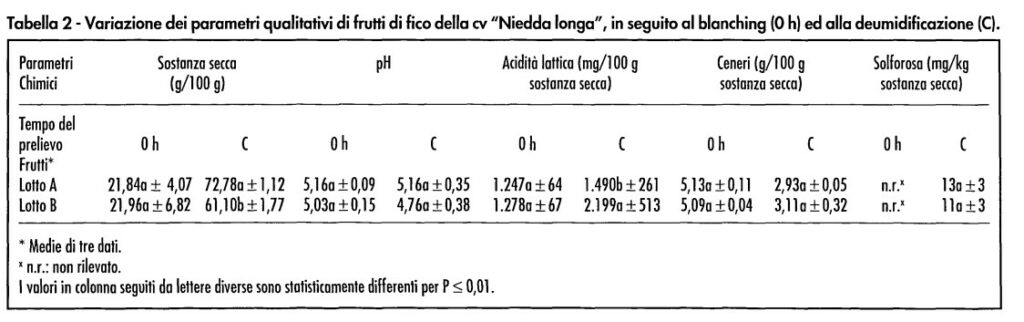

Taking into consideration the variation of the dry matter content of the fruit, as an evaluation parameter of the technological process, some considerations can be noted. As regards the fruits of batch A (fig. 2), they were influenced in a different way, during the test, by the dehumidification environment. In summary: a) during the first 24 hours of dehumidification there were no appreciable variations in this parameter; b) in the second 24 hours the dry substance doubled its percentage value passing from 21.1 ± 3.07% to 47.9 ± 2.82%, probably due to the lowering of the RH from 140% to 137% (fig. 1); c) during the following 48 h the dry substance of the fruit regularly increased, but with increments lower than those recorded in point b, being affected by the interruption of operation of the dehumidifier after 60 h, which determined a new increase in the RH up to I40%; d) during the last 24 hours a further acceleration of the dry matter increase of the fruit was recorded (with the achievement of the final value of 79.3 ± 0.88%), since the UR content decreased up to 35%. In the fruits of lot B the dry matter varied according to this trend (fig. 2): a) during the first 24 h of dehumidification it increased from 22.0 ± 6.820/0 to 32.1 ± 6.06%, showing a lower dependence on UR with respect to lot A (fig. 1); b) in the following 48 h the drying process proceeded regularly, even if less rapidly than that of the fruits of lot A; c) in the last 24 h, during which the RH value decreased from 38% to 136% (fig. 1), the fruit dry matter increased up to the final value of 69.6 ± 4.74%. Given the differences between the two lots, which also depended on the initial dimensions of the fruits as well as on the different duration of drying, the best dehumidification efficiency was obtained with the combination of 32°C and 35-36% of ambient RH. chemical variations The dry matter content of the fruits of the 2 lots at 0 h (tab. 2) was comparable with what Secchi (1967) reported, vice versa it was lower than that of the variety21 Kalamata, of Turkish origin, uacobs, 1951).

Given that sugars constitute the 70-75% of this parameter Uacobs, 1951; Secchi, 1967), the selection of the fruits to be dried should21 be based not only on their size, but also on their total solids content. The ash content is decidedly higher (tab. 2) which, in the previously cited works, has never been higher than 3.5%. The pH was higher while the lactic acid21 of the fruits of the 2 lots at 0 h was, in this test, lower than what was previously found on the same variety21 (Piga et al., 1995). The characteristics of the dried fruits, determined again at the time of packaging following the storage at ambient temperature and relative humidity21, were decidedly influenced by the different dehumidification duration of the 2 lots (tab. 2). The fruits of the two lots in fact underwent a partial rehydration, those of lot B, then, were significantly characterized not only by the lower content of dry matter, but also by a higher acidity, compared to the fruits of lot A. II strong lowering of the ash content which was observed during the dehumidification process in the 2 lots, can be attributed to the percolation of the juice from the fruit ostiol. Finally, the limited total sulfur content of the 2 lots seems to be attributable to a simple phenomenon of concentration of its natural level. The composition of the figs of lot A was comparable to that of the imported fruits (table 3), even if with a lower dry matter content. The ash value of commercially available dried fruits (tab. 3), similar to those of lot A and lot B (tab. 2), suggests that the juice losses during dehumidification were not influenced in a different way than traditional drying. The low sulfur dioxide content of imported products may be due to the excellent degree of use of this preservative by manufacturing companies in Asia Minor, which allows them to deliver a product to customs in accordance with the law as regards the limit maximum of this parameter. The figs of lot B differed from the imported products not only for the lower dry matter content, but also for their greater . king acidity. Compared to industrially dried figs (Harris and Von Loesecke, 1960), the lower dry matter content of the productions of this trial was confirmed, which was, on the contrary, higher than sun-dried national productions (Secchi, 1967).

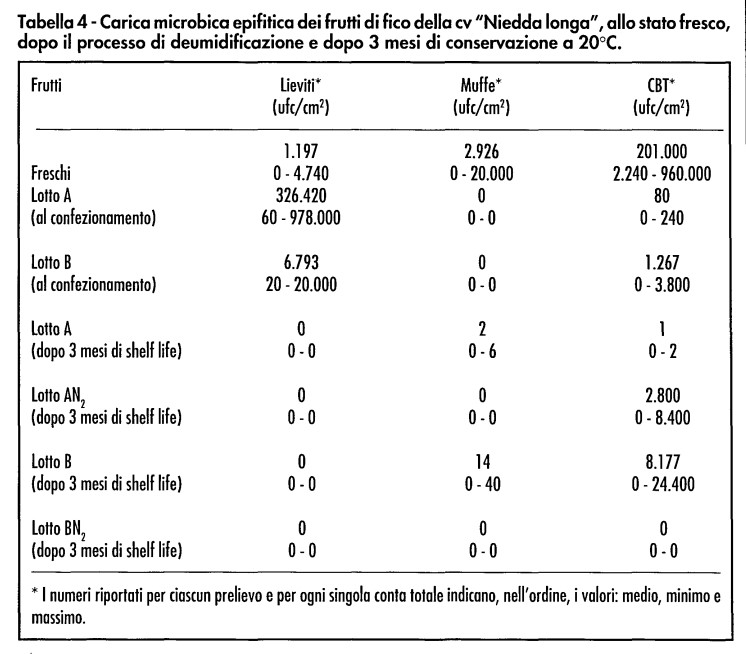

microbiological aspects

The CBT decreased passing from the fresh fruit to all the processing and conservation lots considered (table 4). Conversely, the adaptation model of the yeast species differed between the lots at the time of packaging, compared to the same after the 3 months of shelf life. The moulds, in high numbers on the fresh product, were no longer present at the time of packaging, just as the modified atmosphere packaging controlled the development of these pathogens at the end of the shelf life. The results relating to CBT, at the end of the shelf-life, were instead conflicting. However, in general, at the end of this storage period, the count values of the 3 microbial groups of dehumidified figs (tab. 4), were comparable with those found on commercia II products (tab. 3), showing good microbiological stability of the dried product, certainly also due to the use of potassium sorbate.

CONCLUSIONS

The dehumidification course observed on fruits of different sizes therefore leads to having to consider both the sorting based on the minimum content of total solids and the calibration of the syconia, before drying, as appropriate. All this for the need to obtain a better control of the technological process for a greater homogeneity of the final characteristics of the product.

The choice of this technological treatment, which leads to the production of dried figs still sufficiently rich in humidity, makes the treatment combined with potassium sorbate mandatory. This supplementary treatment, carried out on the fruit before packaging, leads to a certain reduction in the total microbial load, which packaging with modified atmosphere has not, on the contrary, shown. With regard to the dehumidification technological process alone, it seems decisive to extend it to at least 120 hours, taking care to keep the temperature and RH (Relative Humidity) values of the air constant at 32° (and 35-36%).

Contact us for information

Address

via Ammiraglio Millo, 9 (Alberobello – Bari)

info@ailovetourism.com

Phone

+39 339 5856822